What's Your Gardening Zone? Wildfire Smoke vs Your Plants.

Plus, helping new plants survive their first winter.

More information about what you heard on Episode 134 of the Garden Basics with Farmer Fred podcast. Or what I hope you will hear. Topics covered on Ep. 134 include:

Winter protection of young perennials and woody plants in cold climates.

Understanding USDA Zones (and the Sunset Garden Zones).

Wildfire Smoke and Your Garden.

Deciphering USDA Plant Hardiness Zones

(and Sunset Garden Zones, too!)

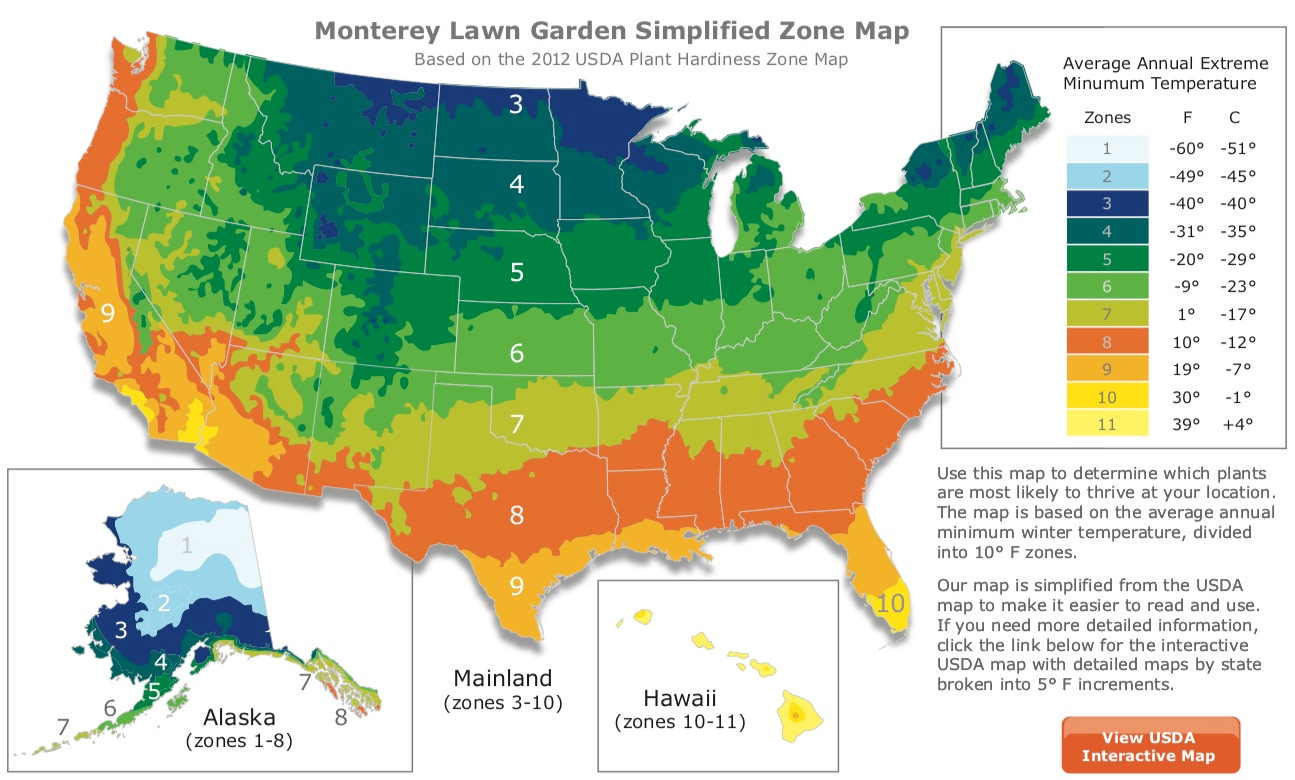

Finding a USDA Plant Hardiness Zone map that you can actually decipher can be a hunt. Monterey Lawn and Garden Products made it simple for us. Go to their link to use that USDA Interactive Map Link. By the way, kudos to Monterey Lawn and Garden Products. They are one of the few garden chemical companies to put all their product labels on line and easy to find. And, you’ll find it in the header on that link above.

Here is the USDA’s version of their own map. Not bad, but definitely not as complete as the one above.

How to Understand Plant Hardiness Zones

(adapted from Wikihow: https://www.wikihow.com/Understand-Plant-Hardiness-Zones)

USDA Hardiness zones were created to help home gardeners and nursery owners make informed decisions about what plants will perform well in certain areas. The USDA hardiness zone map has undergone many versions through the years.

Hardiness zones are based on regional low temperatures, more exactly the Average Annual Extreme Minimum Temperature. Each zone is further divided into subzone a or b. For instance, here in USDA Zone 9, that extreme minimum temperature is pegged at 19-30 degrees, with 9a at 19-25 degrees and 9b, a bit less cold on extreme days, 25-30 degrees. Most plant tags and references to USDA Plant Hardiness zones stick to the whole numbers. They do not usually delve into the letters.

There’s about a 10 degree Fahrenheit difference from a whole zone to the next.

Probably the most common place to make mention of USDA zones are on the plant tags at your local nursery. A good reason to know the USDA zone you live in, especially if you live in an area that borders on two zones. To figure out your USDA Zone, you may have to do some squinting at small, color coded maps. Or, visit the USDA Plant Hardiness home page online, at https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov

Here’s a rough idea of the USDA Zones across the country. Remember, they reflect the average annual extreme minimum temperature only, which isn’t much data, really, to successfully garden by. Still, it’s the most widely used reference in the nursery business.

Alaska and Hawaii comprise the extreme ends of that low temperature reference guide, with immense Alaska include zones one through eight, roughly temperatures that go from 60 below zero to 10 above zero. Hawaii is on the other end of the temperature spectrum, a state that include Zone 11 (where temperatures are not anticipated to fall below 39 degrees) to Zone 9, which is primarily in the interior of the big island.

In the continental US, Zone 10 can be found in southern Florida and parts of southern California and parts of Arizona. Zone 9 encompasses much of the interior of California and what might be considered the area around Interstate 8, extending from southern California, south Texas and northern Florida.

Zone 8, where extreme lows on average are around 10 degrees, includes some of the middle elevations of California as well as much of southern Arizona and New Mexico, and traveling through the Sunbelt of Texas, Louisiana, southern Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina and much of coastal North Carolina.

Zone 7, where lows can reach 1degree above zero, include much of the intermountain west, as well as north Texas, Oklahoma, northern Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, parts of northern Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia, along with Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, southern New Jersey and parts of southern New York and Pennsylvania. Most of the plants we talk about on the Garden Basics podcast are suitable for USDA Zones 7 through 9, and possibly 6 and 10.

That’s one of the beauties of the USDA Zone maps, if you have the right microclimate, you may be able to stretch those zones up or down by one.

Throughout the western U.S., most of the area is USDA Zones 6 through 9….until you get east of the Rockies, then the colder zones of 5, 4, and 3 rule in the upper midwest and the northeast. But again, there are exceptions.

One of the best reasons for using the USDA guide to help you pick out plants: a perennial that is classified as being for zones 8 to 10 would probably not survive the winter in zone 6.

Most Californians garden in USDA zone 9, where winter lows average 20-30 degrees. But there’s a big difference in the plant palate between zones 9a (20-25 degree average winter lows) and 9b (25-30 degree lows).

Again, go visit the USDA Plant Hardiness home page online, at https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov.

While the average low temperature in the winter is a big factor in determining which plants will grow in your zone, the average high summer temperatures must also be considered.

Many plants cannot take the heat in hot climates; or, they need a pronounced winter chill to bloom. This high end of a plant’s temperature tolerance is actually taken into consideration when a plant is assigned a zone range.

For instance, the gorgeous winter blooming witch hazel (Hamamelis) is a very common plant in the eastern U.S. and other areas with below freezing winter temperatures. In California and many warm winter areas? It’s not so common.

Play it safe. Take the ever-fluctuating climate into consideration when selecting trees, shrubs and perennials. All areas throughout the United States experience unusual highs and lows from time to time.

Determine your Hardiness Zone then choose plants that are rated hardy for at least one Zone higher and one Zone lower to insure the plant will survive an unexpected extreme.

Consider whether you live within a microclimate. Living in warmer climates in the west, south and along the coast can make finding your gardening zone a little more complicated. These areas are riddled with microclimates that are influenced by elevation, humidity (or the lack of it), wind patterns and more.

And that brings us to a superior but harder to find reference for climate and plant adaptability, the Sunset Garden Climate Zone maps.

Gardeners in the Western United States are very familiar with the Sunset Western Garden Book, which divides the west into 24 different zones. Sunset recognized that a plant's performance is governed by the total climate: length of growing season, timing and amount of rainfall, winter lows, summer highs, humidity, persistent wind patterns. Sunset's climate zone maps take all these factors into account.

And, at one time, Sunset produced a National Garden Book, whose climate zone maps were broken down into 45 different zones, definitely a superior system to the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone maps. Here’s a great link (and easier to read) version of that U.S. map of Sunset Gardening Zones, on Gary Ibsen’s tomatofest.com website.

However, the Sunset National Maps, as well as the National Garden Book, are out of print. Why? For that portion of the story, we turned to a longtime editor of Sunset’s garden books, Lance Walheim. Listen to what he had to say in Episode 134 of the Garden Basics podcast.

But, a quick look online can score you an old copy!

Wildfire Smoke vs. Your Garden

Once again, the Central Valley is entering into another new, unwanted season of falling ash and wildfire smoke. We know the ill effects of breathing smoke on us gardeners. And, yes, your flowers and vegetables do suffer on these smoky days, as well. Surprisingly, there’s some benefit to your plants from all this smoke. But first, the bad news.

Dr. Lew Feldman, the Garden Director of the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden, points out that the combination of the toxic chemicals in the smoke is suffocating your plants.

“Chemically, more than 100 different compounds have been identified in smoke, including toxic levels of nitrous oxide, sulfur dioxide and ozone,” Feldman writes in the Garden’s monthly newsletter.

“Short-term exposure to smoke, as little as 20 minutes, has been reported to reduce photosynthesis by as much as 50%, as a consequence of both the destruction of chlorophyll, the light-capturing green pigment, and in impeding the movement of carbon dioxide into the plant through leaf pores.”

Feldman points out that the effect is usually accompanied by a lessening in plant growth, including a reduction in fruit production and in slowed ripening. And, as any local winemaker can tell you, that prolonged exposure of fruits and vegetables to smoke can affect their taste.

When falling ash accompanies the smoke, Feldman says that stresses the plant even more. “When ash lodges in a pore, not only is the intake of carbon dioxide retarded, but the pore can no longer function efficiently in preventing water loss from the plant,” says Feldman. “As a consequence, this increases the likelihood of the plant suffering from water stress.”

Feldman explains there may be a silver lining to the ash fall. “Ash is organic matter, composed of many of the essential nutrients that plants require, including calcium, magnesium and potassium,” says Feldman. “So, if the ash accumulation is not so great as to bury the plant, the ash can be thought of as acting as a fertilizer. That said, we can assist our plants in recovering from ash coatings by irrigating the plant and by hosing down the leaves and the fruits.”

And, there is another, if contradictory, benefit to smoky skies for your plants, according to the “Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences”. Researchers in the January 2020 report indicate that wildfire smoke could increase plant productivity. They studied the ecological effect of wildfire smoke in the Central Valley during the summer of 2018. They found that the increase in production was due to the smoke scattering incoming sunlight, allowing the sun's energy to reach further into dense plant canopies. That increased the efficiency by which these plant canopies photosynthesized, leading to productivity increases. However, the researchers note, there are trade-offs with total light and other pollutants.

And it’s those “trade-offs” that should concern gardeners. If you are diligent about washing off smoke and ash particles from all surfaces of the leaves on a regular basis during wildfire events, your plants will be able to respire normally, reduce possible water stress, and resume thriving. And if you are outside working on a smoky day, take precautions when working, especially if it involves ash cleanup.

Don’t forget, you want to clean ash off both the tops and bottoms of the leaves.

A long outdoor water wand with an angled head equipped with a shower spray can make that task a lot easier.

The Farmer Fred Minute: As discussed in the Q&A segment of Episode 134 of the Garden Basics podcast, Prof. Debbie Flower advised gardeners in freezing areas to baby their one year old (or less) fruit bearing shrubs, small trees and perennials, such as a new pomegranate bush:

But, I wondered…is it OK to add all that mulch BEFORE the first freeze, instead of waiting until afterwards? Debbie says: “You can mulch before soil freezes. Soil will then freeze when temperatures get low enough and it will stay frozen as long as mulch keeps the soil shaded.” So, add that task to your to-do list before your typical first freeze. Or, be ready to swing into action afterwards!

And finally…

Thanks for Subscribing and Spreading the Word About the Garden Basics with Farmer Fred newsletter, I appreciate your support.

And thank you for listening to the Garden Basics with Farmer Fred podcast! It’s available wherever you get your podcasts. Please share it with your garden friends.

(As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases from possible links mentioned here.)